Tom Andronas Producer – video | radio | print | photo+61 412 371 466

tomandronas(at)gmail.com

“Terror and Desperation” – Neos Kosmos

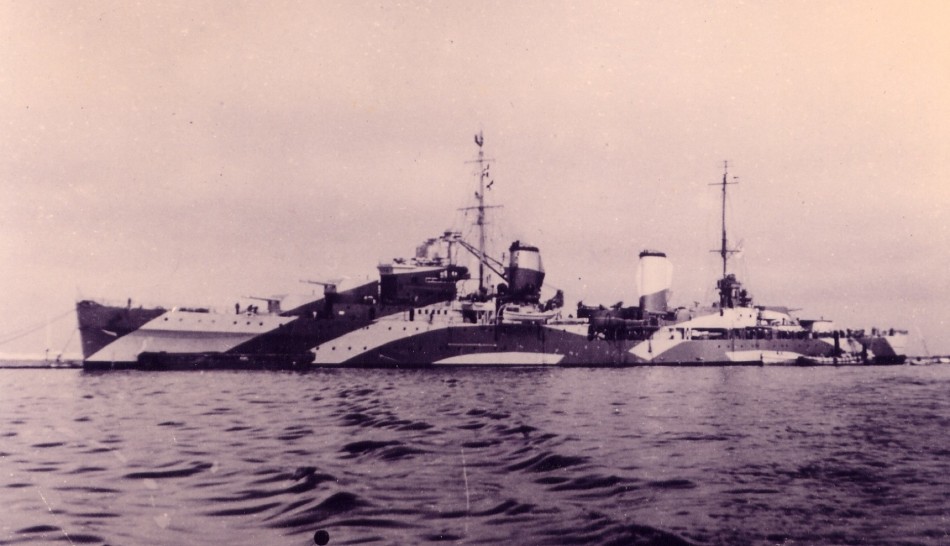

The HMAS Perth in the Mediterranean. Photo: Archive

The HMAS Perth in the Mediterranean. Photo: Archive

21 May 2011

THOMAS ANDRONAS

“When the Greeks were invaded by the Germans I was standing up on the Acropolis watching the harbour being bombed.”

Basil Hayler, now 89 was a 19 year-old sailor on the Australian warship HMAS Perth when he watched the bombs rain down on Athens in 1941.

His actions and sacrifices, along with the thousands of other Anzacs who served in Greece in World War II, helped to ensure that we now live in a vibrant, democratic and culturally diverse nation.

Gordon Beal, now 92, sailed into Piraeus as a member of the 2nd/8th Australian Field Engineers. In the same flotilla was Tom Morris, now 94 but then an infantryman in the 2nd/5th Battalion.

“By the time we got to Piraeus, it had been badly bombed by the Germans,” says Mr Beal.

“The scheme was for everybody to get to Salonika but by then the Germans were already [there]. But we did get as far north as Elasson. From there we were put into the mountains where the infantry had formed a line.”

Tom Morris was in that line.

“Word came through we were to retreat…Honestly, not one of us wanted to go back, we wanted to go on and have a crack at Gerry, that’s what we went there for and what we wanted to do,” Mr Morris says.

“The looks on the Greek faces as we went in were hope, and then as they saw we were going on through, it was just despair,” he says.

On that march Tom Morris’ unit was bombed by a low-flying German Stuka. He was hit on the back by a chunk of rock, an injury the burdens of which he still carries today.

As the infantry withdrew from mainland Greece Gordon Beal’s engineers were readying to delay the German advance.

“We’d do our very best to make a terrible mess, to slow down anyone that was coming,” Mr Beal says.

“We gradually leapfrogged all the way back until the 28th April when we were eventually evacuated from a small fishing village in southern Greece.”

“We’d sneak in, in the middle of the night, and pick them up off the south coast of Greece, uncharted waters, black as night, silence,” says sailor Basil Hayler.

Tom Morris was also evacuated from the southern mainland. From there his unit was convoyed to Alexandria and that was the end of his Greek campaign. Others, like Gordon Beal were ferried on to Crete.

At a small campsite to the east of Souda Bay, Gordon Beal’s engineer unit was informed by their commanding officer that he had volunteered them to stay for the defence of the island. But without gear, which had set sail for Alexandria, they were essentially reduced to an infantry unit.

“The only equipment we had was rifles,” Mr Beal says.

Then came the airborne German land invasion. Basil Hayler watched it from the deck of the HMAS Perth.

“We watched the troop carriers…towing their gliders. They looked like ants running along the horizon,” he says.

“After the paratroopers landed of course we had to stop the seaborne invasion, which we did successfully, one of the few successes we had in the war up until that time.”

“Then the action got a bit too hot, we were bombed badly and ships were being sunk everywhere. I watched 5 ships go down around us.”

“That was on 21st may 1941, one of the hottest days of bombing we had.”

According to Mr Hayler, the warships Juno, Gloucester, Fiji, Greyhound, Kashmir and Kelly were all hit.

As Basil Hayler watched the German ants dropping from the sky, Gordon Beal was awaiting them on the ground, .303 rifle in hand.

His unit of engineers-cum-infantrymen had been positioned on the back of a hill near the Rethymnon airstrip, behind the 2nd/1st Australian infantry battalion.

He says that even though they had been warned that the invasion would come from the sky, there are still no words to describe the sight of the paratroopers dropping towards them.

“Sheer terror and utter desperation…Everything you do becomes automatic. You think, ‘they’re coming for me’,” he says.

“You just don’t know how its going to end but somehow or other you do what you’re supposed to do. I suppose the sensible thing to do would have been to run away.”

“When the war finished you say, ‘I’m here, I survived it’, and quite a few of my mates hadn’t.”

On the day of the invasion, Gordon Beal had been tasked with running messages between officers.

“[The] instructions were simple, the only Germans that were to be allowed on that airstrip were either to be dead or they’ve put their hands up, surrendered. And that’s the way it was…Very quickly, 500 were dead, 500 were POWs and a few of them had bolted towards Heraklion,” Mr Beal says.

After ten days of fighting, Crete fell to the Germans. The surviving warships, including Basil Hayler’s HMAS Perth were sent in by night to evacuate troops from the south side of the island.

“We loaded up roughly a thousand soldiers and on the way back to Alexandria we got hit by a bomb. That killed about eight soldiers and four sailors and that, as far as we were concerned, was the end of the Greece/Crete campaign.”

Before they could be evacuated, Gordon Beal’s unit was overrun by the Germans.

The last instruction his commanding officer gave was that the unit’s German prisoners were to be protected from the Cretans until the rest of the German troops arrived.

“They really needed that protection because it’s a fact that the local people were absolutely fantastic. They came from everywhere and Lord help you if you were a German,” Mr Beal says.

But the lasting memory of the Greek campaign for these extraordinary men is one of futility.

“Every man that went to Greece wanted to keep fighting and face the enemy but we were ordered back, and there was nothing we could do about it,” Tom Morris says.

“And to see the looks on the faces of the people of Greece, the hopelessness in their eyes when we were departing just tore me apart. I’ve always had the greatest respect for the Greek people.”

Gordon Beal shares Tom Morris’ esteem of the nation they fought to defend.

“[Greece] was the only place, really the only country in Europe that really stood up and opposed the Germans. So for that nation to have done that was an absolutely fantastic thing, and they made us very, very welcome.”

“The Cretans had thrown the Turks out…they were warriors. I could never ever do anything but feel sorry that we failed, and we did. But they were marvelous, they still are. They still love us,” he says, lowering his voice, but with a smile.

Having been overrun, Gordon Beal’s unit was taken prisoner by the Germans. He was transported through Greece to Germany where he spent a bitter winter unfreezing railway tracks. He later discovered that opposite the POW camp, was the Dachau concentration camp.

After four years as a prisoner of war, Gordon Beal was liberated by US forces. He spent several weeks receiving medical treatment for his severe malnourishment, before being shipped back to Australia.

Gordon Beal now lives in Williamstown, Victoria with his wife Audrey.

Basil Hayler lives in Ferntree Gully, in Melbourne’s east.

Tom Morris lives with his wife Doris in the Victorian border town of Corowa.

All three are magnificent, humble men who deserve our utmost respect, and our sincere thanks.